What the Hell Does “Conservative” Even Mean These Days?

As you’ve probably heard by now, last week the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit finally explained its reasoning in overturning a lower court’s ruling issuing an injunction against enforcement of a new Texas law which most people still refer to as “House Bill 20”. It’s a statute purportedly designed to prohibit large, popular social media platforms from censoring speech based on the viewpoint of the user/speaker.

As you’ve probably heard by now, last week the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit finally explained its reasoning in overturning a lower court’s ruling issuing an injunction against enforcement of a new Texas law which most people still refer to as “House Bill 20”. It’s a statute purportedly designed to prohibit large, popular social media platforms from censoring speech based on the viewpoint of the user/speaker.

In doing so, two-thirds of the Fifth Circuit panel clearly believes they have done something to protect the First Amendment rights of Texans. But, for those of us who believe the clear role of the First Amendment is to prevent the U.S. government from restricting speech, while also protecting the right of private companies to exercise editorial control over their own publications and platforms, what the court has done is squelch the First Amendment rights of a select group of private entities.

Judge Andrew S. Oldham, who penned the ruling for the panel’s majority, was appointed to his current position by former reality TV show host Donald J. Trump and at one time served as General Counsel to Texas Governor Greg Abbott. The other two judges on the panel, Edith Jones and Leslie Southwick, were appointed by Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, respectively.

That all three appellate judges were appointed by Republicans, along with the fact the case involves a statute clearly inspired by the desire to prevent censorship of conservative political expression, has led a lot of observers to conclude this decision was driven by the conservative ideology of the jurists who handed it down. If so, theirs seems a confused and non-traditional conservatism, because this decision is about as far as it gets from the ‘just call balls and strikes’ approach conservatives have long advocated for judges to employ.

For starters, evidently the old line that “corporations are people, too”, not so long ago championed and echoed by a Republican nominee for President, only goes so far with conservatives these days – or only goes so far with the conservatives sitting on this Fifth Circuit panel, at least.

(As a quick aside, if you’re one of those people who insists that a company being publicly traded makes it a “public company”, there’s likely nothing I can say that will penetrate your willful ignorance on this subject, so you can just stop reading right here.)

In terms of judicial conservatism, a legal philosophy that purportedly encourages jurists to set aside their personal preferences and perspectives and rule based on law and precedent, rather than issue outcome-oriented decisions, the Fifth Circuit has strayed even further from traditional conservatism.

Speaking about the decision in a live stream broadcast shortly after the court issued its ruling, attorney Corbin K. Barthold, who serves as Internet Policy Counsel and Director of Appellate Litigation for TechFreedom, offered what he called “a conservative’s approach to why you should not like this decision.”

“For those of you who are lawyers out there and who have been in the space for a long time, the way I would summarize this decision in a single sentence is: This decision is the mirror image of whatever your least favorite 9th Circuit opinion of all time is, whichever one you read and you saw as completely results-oriented and completely reverse-engineered, where every lawyer trick and rhetorical device was purposely wielded in a partisan way,” Barthold said. “That is what is going on here and at the very least you should recognize as you read it, if it makes you happy, that is what’s happening.”

Granted, some folks who are undeniably conservative, like Justice Clarence Thomas of the U.S. Supreme Court, have advocated for treating social media platforms like “common carriers”, as the Fifth Circuit appears to have done in this decision. But even Justice Thomas doesn’t claim that’s how the law treats social media platforms currently; he just believes this is how the law should treat such platforms.

Let’s say legislatures around the country adopt Thomas’ suggestion and pass laws declaring social media platforms to be common carriers, or akin to such under the law; clearly this would have massive implications, not just for the platforms, but for all of us who use them. The idea raises a host of questions.

What outcomes would this legal and policy change have on the market? Have conservatives abandoned the notion that the government should take laissez faire approach to regulation entirely, or are they just very selectively picking winners in a laissez faire sweepstakes of some kind? Have conservatives like Thomas fully thought this through from their typically anti-regulation perspective?

Are social media platforms particularly similar to telecom or utility companies, in terms of the services offered? Are the contents of private phone calls – typically audible only to the call’s participants, absent invasive third-party monitoring of some kind – truly analogous to the content of Facebook posts or tweets, which are generally visible to large groups of readers and viewers, not to mention the platform’s advertisers?

Shouldn’t a business be able to deny space on its platform to speech that sends its advertisers into a frenzy over the potential for bad PR, stemming from their ads being displayed next to some manner of lunacy that may be protected by the First Amendment, but certainly isn’t the sort of thing with which they want their brand to be associated?

Ilya Somin, a professor of law at George Mason University and frequent contributor to the Libertarian-leaning law blog Volokh Conspiracy, called the Texas law “a menace to free speech” in a post he published in May. In the post, Somin provided a compelling argument to support his description of the law.

“Both the right to free expression and the right to refuse a platform to speech you disapprove of are vital elements of freedom of speech,” Somin observed. “If Fox were forced to broadcast left-wing views they object to and the (New York) Times had to give space to right-wing ones its editors would prefer to avoid, it would be an obvious violation of their rights. Moreover, in the long run, such policies would actually reduce the quantity and quality of expression overall, as people would be less likely to establish TV stations and newspapers in the first place, if the cost of doing so was being forced to give a platform to your adversaries’ views… Thus, there should be a very strong presumption against forcing people to provide platforms for views they object to. Can proposals for common carrier regulation of social media overcome that objection? The answer should be a firm ‘no.’”

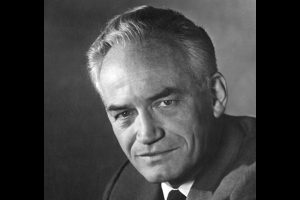

Much has been made of one line in the court’s decision: “Today we reject the idea that corporations have a freewheeling First Amendment right to censor what people say.” Instead, it seems this court believes the government has a freewheeling right to tell private companies what expression they must host and to which they must provide a forum! If you’re even a little bit “conservative” as that term has been defined over my 50+ years on this planet, this notion ought to send a cold chill down your spine – if not cause a life-size vision of Barry Goldwater to pop up and scream “Noooooooo!!” right there in your fucking living room as you think about it.

If you identify as a conservative and you think this decision is a good thing, consider this hypothetical: Suppose an evangelical Christian bakery ever becomes the dominant market force in some small town somewhere, to the point where every married-couple-to-be in that town has three choices: (1) Have their wedding cake made by that market-dominant bakery; (2) go to a bakery in a different town/market to get their wedding cake made; or (3), make their own damn wedding cake.

In the above scenario, would this Fifth Circuit panel hold that our hypothetical, market-dominant baker doesn’t have a First Amendment right to refuse to make a wedding cake for a same-sex wedding, despite the bakery’s presumably “sincerely held religious belief” that same-sex marriage is immoral and against the will of God? Or is freewheeling corporate censorship inherently more palatable (or state mandated speech less so) when it comes in the form of a confection denied for reasons sourced from the Old Testament? If so, can Twitter just say it has a sincerely held religious belief that Donald Trump should fuck right off and keep his ban in place indefinitely, or does the lack of reference to tweeting in the Bible simply rule out that possibility?

One more question for you, good judges of the Fifth Circuit, which I’m going to borrow from some random guy on Twitter:

Does this mean Truth Social won’t be able to ban speech negative of Trump?

— Ian (@IanMCohen) September 16, 2022

Oh, and in case you’re wondering whether this new Texas law would prohibit platforms from banning or removing sexually explicit content — material presumed to be protected by the First Amendment until and unless deemed “obscene” by a trier of fact — the answer is a resounding “No”. House Bill 20 carves out a clear exception, not just for obscene material, but for “material depicting sexual conduct”, as well.

Yes, you read that right: Apparently, when it comes to sexually explicit expression, freewheeling private sector censorship is still just fine by the Fifth Circuit. Funny how that works.

Barry Goldwater portrait image is a work of the federal government and in the public domain