The History of Obscenity Laws in the United States (Part 3)

Two weeks ago we introduced our series on The History of Obscenity Laws in the United States, which is intended to bring adult industry participants up to speed on how these laws formed and evolved in the US, and how they impact (and stifle) creators and distributors.

Two weeks ago we introduced our series on The History of Obscenity Laws in the United States, which is intended to bring adult industry participants up to speed on how these laws formed and evolved in the US, and how they impact (and stifle) creators and distributors.

Last week in Part 2 we examined in some detail the early history of obscenity laws in America, including early colonial cases, plus the rise of Anthony Comstock and the Comstock Laws; we also discussed notable victims of Comstock’s crusade. In this third entry to the series, we’ll move on to discuss the evolving nature of how courts have attempted to define obscenity in America, an elusive goal and surprisingly difficult legal challenge, as you’ll see below.

The Hicklin Test: Early Obscenity Standards

The origins of modern obscenity standards in the United States can be traced back to English common law, which has significantly influenced American legal principles since the country’s founding. A pivotal case in this regard is the 1868 English case Regina v. Hicklin. This case involved the sale of a pamphlet titled “The Confessional Unmasked,” which criticized the Catholic Church’s confessional practices. The pamphlet was deemed obscene under the judgment of Chief Justice Alexander Cockburn, an English judge. Cockburn’s ruling established what became known as the Hicklin Test, which defined obscene material as anything with the potential “to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.”

Hicklin’s Focus on Isolated Passages

The Hicklin Test is worth remembering because it marked a significant shift in legal standards for obscenity. It focused on the effect of isolated passages on particularly susceptible individuals, such as children, rather than considering the work as a whole. This meant that if any part of a publication could potentially “corrupt” vulnerable minds, the entire work could be deemed obscene and thus subject to censorship.

This broad and restrictive standard was soon adopted in the United States, of course, where it had a profound impact on the country’s legal landscape. One of the earliest and most notable applications of the Hicklin Test in the U.S. was in the case of United States v. Bennett in 1879. The case involved the prosecution of D.M. Bennett, the publisher of a New York-based free-thought periodical. Bennett was accused of mailing allegedly “obscene” material. The court applied the Hicklin Test to determine whether the content could corrupt susceptible minds, leading to Bennett’s conviction. This case highlighted the Hicklin Test’s influence on American obscenity law, setting a precedent for subsequent cases.

The Hicklin Test’s focus on the potential effect of specific passages (rather than the work as a whole) often resulted in the suppression of important literary and artistic works. This restrictive approach faced growing criticism over time, particularly as it often failed to account for the context, intent, and overall merit of a work. Critics argued that the test was overly broad and could be used to censor works that were not intended to corrupt or deprave but instead had artistic, literary, or educational value.

The Hicklin Test in Action: Banning James Joyce

A notable and controversial case that applied the Hicklin Test (and helped pave the way for the Roth v. United States decision, discussed below) was United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses” (1933). This case centered on James Joyce’s novel “Ulysses,” now a common read for English Literature majors everywhere — but initially banned in the United States as “obscenity” under the Comstock laws.

In 1933, Random House, with the intention of publishing “Ulysses” in the U.S., sought a legal ruling on its obscenity status by arranging for a copy to be sent to the country and seized by customs. This act is what led to the aforementioned case United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses”, which was presided over by Judge John M. Woolsey in the Southern District of New York.

Why did Random House seek a ruling before simply publishing the novel? To understand that we need to jump backwards a few years.

“Ulysses” was first serialized in the American literary magazine “The Little Review” from 1918 to 1920. However, in 1921, the U.S. Post Office seized and burned copies of the magazine containing the “Nausicaa” episode, leading to an obscenity trial against the magazine’s editors, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap. The court found the material “obscene” under the Hicklin Test, ruling that isolated passages were capable of corrupting minds open to such influences, particularly focusing on descriptions of a character’s sexual arousal. Anderson and Heap were sentenced to six months in prison each, however the judge suspended the prison sentence and they were instead fined $100 each.

The Hicklin Test, which remember focused on isolated passages and their potential effect on the most susceptible members of society, deemed the entire work obscene if any part of it could be considered so. This broad application had resulted in the suppression of “Ulysses” in the United States, which in turn had sparked significant controversy and debate over censorship, artistic freedom, and the limitations of the Hicklin Test. Critics argued that the test was outdated and overly broad, failing to consider the literary value of the work as a whole. Random House sought to platform these arguments in United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses”.

Judge Woolsey’s Ruling and Impact

Judge Woolsey agreed with the defendants and rejected the Hicklin Test’s narrow focus on isolated passages, instead examining the book as a whole and considering its artistic merit. In his decision, Woolsey declared that “Ulysses” was not obscene, emphasizing that the intent of the author was to create a literary masterpiece rather than to arouse prurient (that word again!) interest. He noted that the book’s treatment of sexuality was realistic rather than obscene, arguing that the law should protect literary works with significant artistic value.

Judge Woolsey’s ruling was groundbreaking, as it set a new precedent for evaluating alleged obscenity, considering the work in its entirety and acknowledging its artistic merit. This decision marked a shift away from the Hicklin Test towards a more nuanced approach, laying the groundwork for future challenges to restrictive obscenity laws.

The Ulysses case was a critical moment in the evolution of obscenity law in the United States. It demonstrated the limitations of the Hicklin Test and highlighted the need for a more balanced approach that considered both community standards and the overall value of the work. This shift in judicial thinking paved the way for the Supreme Court’s decision in Roth v. United States (1957).

Shifts in the 20th Century: Roth v. United States (1957)

As the 20th Century pressed on, American society continued to evolve and attitudes towards sexuality and free expression became more liberal. There was a growing movement to replace the Hicklin Test with a standard that better reflected contemporary values and legal principles. This shift eventually culminated in the landmark Supreme Court decision Roth v. United States (1957), which rejected the Hicklin Test and established a new standard for obscenity in U.S. law.

Samuel Roth, a publisher and bookseller, had been convicted under a federal statute for distributing “obscene” materials. The Supreme Court, in a landmark decision, redefined obscenity in a more limited and specific way. Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., writing for the majority, held that obscenity was not protected under the First Amendment, but he set a new standard for determining what constituted obscene material.

The Court in Roth declared that material was obscene if, to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material, taken as a whole, appealed to prurient interest. This new test emphasized the perspective of the “average person” rather than the most susceptible, and required that the material be judged in its entirety, rather than by isolated excerpts. The Roth decision thus narrowed the scope of what could be deemed obscene and allowed for greater artistic and literary expression.

Problems with Roth

The Roth standard lasted for several decades, but while Roth was a big improvement over Hicklin, it still proved problematic for free expression.

Critics argued that the term “prurient interest” was too vague and subjective. The Roth test defined obscenity as material that “to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, appeals to the prurient interest.” This reliance on what might appeal to a “prurient interest” left much room for interpretation, leading to inconsistent rulings across different jurisdictions.

The Roth decision relied heavily on “contemporary community standards” to judge whether material was obscene, which was problematic because these standards could vary widely from one community to another. This variability also led to a lack of uniformity in rulings across different jurisdictions, also making the enforcement of obscenity laws uneven and often unpredictable.

Also under Roth, material could be deemed obscene if, taken as a whole, it lacked serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. However, the decision did not clearly outline how to assess the work in its entirety or how to evaluate its “serious value,” leading to confusion and even more inconsistent applications.

The Miller Test: A New Standard for Obscenity

The most significant development in U.S. obscenity law came with the Supreme Court case Miller v. California in 1973. This case resulted in the establishment of the “Miller Test,” which remains the standard for determining obscenity to this day.

Marvin Miller was convicted under California law for distributing advertisements depicting sexual activities. The Supreme Court, in a decision delivered by Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, provided a three-pronged test for obscenity, which expanded on the Roth test:

- The Prurient Interest Standard: Whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards,” would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest.

- Patently Offensive Conduct: Whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law.

- Lack of Serious Value: Whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

The Miller Test retained the concept of “community standards” from Roth, but sought to refine it by emphasizing the use of local community standards rather than a vague national standard. This approach acknowledged regional differences in sensibilities and aimed to make the application of the law more consistent within specific jurisdictions.

The Miller decision provided a more structured approach by explicitly including the consideration of whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” This “serious value” clause was intended to protect works (like “Ulysses”) that might have redeeming qualities, even if they contained explicit content, thus narrowing the scope of what could be considered obscene.

The Miller decision also provided more detailed guidance by defining prurient interest in terms of “shameful or morbid” sexual interests. This added clarity helped to narrow the scope of what could be considered obscene, making the legal standard more predictable and easier to apply.

Problems with Miller

While the Miller Test represents quite an evolution from the days of the Comstock Laws, it isn’t without significant problems.

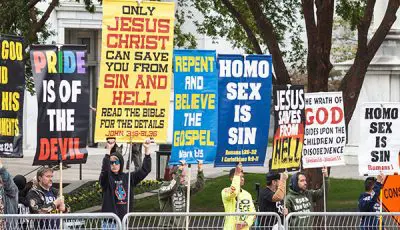

The first prong of the Miller Test relies on “contemporary community standards” to determine what is considered obscene. This approach can lead to subjectivity and inconsistency, as community standards can vary widely across different regions and cultures. What may be deemed obscene in one community might be considered acceptable in another, leading to uneven enforcement and a lack of a uniform national standard.

Keep in mind the Miller Test was established in 1973, and does not adequately reflect the evolving cultural and technological landscape. Changes in societal attitudes towards sexuality and the proliferation of digital media have transformed how people consume and interpret content. The reliance on “local community standards” does not align with the more global and interconnected nature of modern media consumption. Censoring content based on one community’s ideas of what’s appropriate theoretically allows the least tolerant communities to decide what the rest of us can distribute and consume online.

The second prong of the Miller Test requires that the work depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law. The term “patently offensive” is inherently subjective and lacks a clear, objective standard. This ambiguity can also lead to inconsistent application and make it difficult for creators to know what content might be deemed obscene.

The third prong of the Miller Test considers whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” This component is meant to protect works with legitimate cultural or educational merit. However, the concept of “serious value” is vague and subjective, leading to varying interpretations by judges and juries. This lack of clarity can result in the suppression of works that have significant artistic or intellectual contributions. It places significant discretion in the hands of judges and juries to interpret what constitutes obscenity. This discretion can of course lead to inconsistent rulings and the potential for personal biases to influence decisions.

For those who work in the adult industry, one of the last groups in America to still be specifically targeted by obscenity laws, the subjectivity and variability inherent in the Miller Test can make it simply impossible for creators and distributors to predict legal outcomes. For many creators this leads to a cautious approach to content creation and distribution, stifling innovation and creativity in the arts.

What Next?

Now that we’re all caught up on how America got to the Miller Test, and what exactly it is, the next installment in this series will look at the “Golden Age” of pornography (the 1970’s) and some of the key early legal/obscenity battles during that era. We’ll examine some of the landmark cases of that time, and the impact of societal changes on legal standards. Stay tuned!