Getty Accused of Falsely Claiming Rights to Public Domain Images

SEATTLE – In the early days of the online adult industry, I found myself one day spending hour after hour pulling down images from a site I operated. I was doing this because I’d been contacted by the rightsholder to those images, who informed me I was displaying them in violation of their copyrights.

SEATTLE – In the early days of the online adult industry, I found myself one day spending hour after hour pulling down images from a site I operated. I was doing this because I’d been contacted by the rightsholder to those images, who informed me I was displaying them in violation of their copyrights.

I was stunned to receive the call, because I knew I had duly licensed those images from a distributor. The distributor had guaranteed to me in the contract I had signed that their company either owned outright the rights to all the images it distributed or had contracted with the appropriate rightsholder to redistribute the images. In either case, the distributor’s claim was they were legally entitled to redistribute the images I had licensed from them.

As it turned out, they were wrong. Whether they had done so intentionally or in error, the disc the company sent me (yes, adult content providers often mailed around physical discs filled with content back in those days, because downloading or FTP-ing large image sets often wasn’t a viable option) contained images to which the distributor clearly did not have the rights.

I was reminded of that incident today when reading about a proposed class action lawsuit filed in Washington state against Getty Images, Inc. – the company behind image providers like iStock and Thinkstock – in which the plaintiff claims that Getty has been “fraudulently claiming ownership of copyrights in public domain images (which no one owns) and selling fictitious copyright licenses for public domain images (which no one can legally sell).”

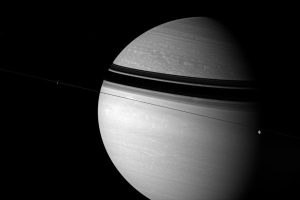

The complaint was filed by CixxFive Concepts, a digital media marketing company based in Texas. According to the complaint, examples of Getty’s alleged misconduct include offering to allow users to purchase a license to a stock photo of Saturn which was authored by NASA, as well as images released by the White House, “such as the famous Osama Bin Laden Situation Room image” in which President Obama and members of his cabinet are intently watching the raid on Bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan unfold.

So, what’s wrong with Getty selling these images and further claiming to have the right to dictate how licensees subsequently use those images?

As CixxFive notes in their complaint, since they’re works of the federal government, these images are in the public domain and not subject to copyright in the first place.

“No one is required to pay Getty and/or Getty US a penny to copy and use them,” CixxFive asserts in its complaint. “And Getty has no right to sell copyright licenses for them, as it has done and is doing.”

Lest one think Getty is providing public domain images on a different basis than the other images in its database, or somehow properly noting them as images not subject to copyright, CixxFive points out that Getty’s “pricing structure for public domain images does not differ in any material way, if in any way at all, from the pricing structure it uses for copyrighted images.”

Getty’s terms for using the public domain images it offers for license don’t differ from those of its copyrighted images, either. CixxFive observes in its complaint that Getty “licenses public domain images using a so-called ‘rights managed’ licensing structure that Getty US itself has claimed allows it to guarantee exclusivity to its licensees.”

The CixxFive complaint cites a case filed by the defendant, Getty Images, Inc. v. Virtual Clinics in which Getty received the statutory maximum damages for copyright violation in part because the court found that “Getty customers who license rights-managed images have exclusive use and control of those images” and “rights-managed images are often used by companies for major advertising campaigns, and customers pay a higher premium for the exclusivity associated with this model.”

As CixxFive notes in its complaint, “Getty US, as the plaintiff in a copyright infringement case, has obtained a $300,000 judgment – the maximum statutory damages available in the case – precisely by successfully arguing that its ‘rights managed’ model was based on exclusivity, which necessarily implicates copyrights and cannot possibly be a part of any public domain photograph ‘license.’ Yet Getty and/or Getty US continues to license public domain images under a ‘rights managed’ licensing model.”

The fact that Getty apparently doesn’t identify public domain images as public domain images is significant for a variety of reasons – not the least of which being that the company employs blanket language which asserts that unless Getty’s site states otherwise, customers are to assume Getty (or someone affiliate with Getty) owns the rights to the images.

“Getty’s and/or Getty US’s website terms agreement also states as follows,” CixxFive observers in its complaint: “‘Unless otherwise indicated, all of the content featured or displayed on the Site, including, but not limited to, text, graphics, data, photographic images, moving images, sound, illustrations, software, and the selection and arrangement thereof (‘Getty Images Content’), is owned by Getty Images, its licensors, or its third-party image partners.’”

Obviously, neither Getty Images, its licensors or any of its “third-party image partners” own images created by NASA, or those shot by an official White House photographer.

Getty has yet to comment on CixxFive’s lawsuit, or to respond to the complaint in court, so it remains to be seen how the company defends itself from these claims. Either way, the allegations serve as a reminder for both licensees and licensors of images: When it comes to the distribution and redistribution of images, the question of copyright goes beyond simply “Who owns this image?” – and goes beyond strictly legal questions, as well.

For example, from a cost perspective, purchasing a license to an image which is in the public domain is the very definition of an unnecessary expense. Nobody can force you to pay for an image that’s in the public domain, nor can they set limits on your use of it. It’s already yours, in effect.

For content creators who license their content for redistribution, the cautionary tale here is that even when you’re dealing with a company which is perceived to be reputable and above-board, it’s wise to keep an eye on how they handle your content after the deal has been struck.

Are they staying within the terms of the license? Are they mixing your content in with that other third-parties as part of a package deal? Does the agreement you have with them permit them to do so? To assure your rights are respected, you’ll need to be vigilant about enforcing them, not just with respect to outright content pirates, but in connection with your marketing and distribution partners, as well.

As with so many other aspects of life and business, at the intersection of copyright and image licensing, the devil is in the details – and to avoid getting burned, you’d best pay close attention to those details.

Image of Saturn by NASA. No NASA endorsement of YNOT.com intended or implied.