Attorneys Weigh In on Offshore Banking, Tax Headaches

By Dennis Taylor

AMSTERDAM – Cross-border taxation and offshore banking were two of the topics attorneys attempted to demystify Saturday afternoon during the Webmaster Access adult industry business conference. Do American businesses need to collect and pay European taxes? Do any safe offshore banking havens remain? Well … yes and no.

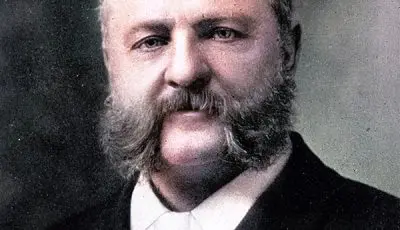

Although Vahe Gevorgyan from Prospectacy was unable to participate as expected, attorneys Michael Fattorosi and Trieu Hoang were present. The legal eagles had only one hour in which to explore their topics, but they gave the standing-room-only audience, split evenly between Americans and Europeans, quite a bit to consider.

Hoang, the attorney for Amsterdam-based AbbyWinters.com, opened with a brief presentation about the European Union’s value-added tax (VAT), which applies to all electronic goods and services. According to Hoang, all businesses, even those located outside the EU, must collect and pay VAT for customers residing in the EU.

Audience members repeatedly challenged Hoang to explain why American businesses should care about EU taxes, considering it’s not clear what penalties they may face for failure to comply with extraterritorial tax laws. How would EU authorities even begin to ascertain what taxes might be due?

Speaking with a slight Australian accent, Hoang revealed American businesses that do not follow EU tax rules could find themselves in a difficult spot if they later chose to expand their banking into EU countries. He also opined that American companies may face continual harassment from EU authorities, possibly with assistance from the American Internal Revenue Service. Apparently, taxing authorities do communicate.

Since VAT rates vary in different EU jurisdictions, the question of which rates to pay was discussed at some length. Multiple scenarios make paying VAT somewhat complicated, Hoang noted.

For example, existing law requires EU companies based in the Netherlands to collect VAT from all customers at the rate applicable in the Netherlands, regardless where in the EU customers are based. Complicating matters, no VAT is due when an EU company sells to a customer who resides outside the EU, but when a business outside the EU sells to customers inside the EU, the customer’s location determines the VAT rate. Therefore, if an American business sells products or services (website memberships or video on demand, for example) to a customer who resides in France, the American business is liable for collecting and paying VAT at the French rate.

Confused yet?

Changes designed to simplify VAT collection and payment are slated to take effect in 2015. When they do, the buyer’s location will be the determining rate factor throughout the EU.

Do current VAT laws mean businesses need to register and pay VAT taxes in every EU jurisdiction? No, Hoang said. Companies may choose just one EU jurisdiction in which to register, and it’s up to the tax authorities in that jurisdiction to collect the company’s payments and distribute them appropriately to every jurisdiction in which the company does business.

That said, businesses do need to track and report their customers’ locations so the proper VAT rates can be applied to each transaction. Location information often can be supplied by a company’s billing provider, according to Hoang. An Epoch.com representative in the audience confirmed Hoang’s assertion.

U.S.-based attorney Michael Fattorosi took up the topic of offshore banking and tax havens.

According to Fattorosi, 30 percent of the world’s wealth currently resides in offshore tax havens. The usefulness of such havens is changing, he noted, because a U.S.-led crackdown on banking secrecy laws around the world has resulted in banks providing details about their customers to U.S. authorities. EU countries have followed the U.S.’s lead, he said, placing additional pressure on banks in traditional tax havens.

The result? Fattorosi said there are few banks left in the world where someone can deposit money and not have to worry about bankers sending information to his or her home country.

“If you have an offshore account, you should probably divulge that information because of potential penalties and what could end up happening to your money,” said Fattorosi.

Some countries have not yet begun sharing information, he added, pointing to Austria, Singapore and Hong Kong, though the latter two have seen increases in transactions in recent years and eventually may bow to pressure. Fattorosi also mentioned Panama as a great banking option — for Panama corporations.

“Over the next five years, you’ll see fewer countries willing to touch [offshore banking],” he warned.

Fattorosi also advised the audience to consider the stability of the economy in any country where they bank, mentioning the recent economic troubles in Cyprus as an example of what can go wrong if a company or individual puts money in a country that experiences an economic collapse.

He pointed out that singer Tina Turner recently renounced her U.S. citizenship in favor of Switzerland, apparently for tax reasons, and he advised that if an individual really wants to hide his or her wealth from one country, such as the United States, that person may have to change citizenship to do it.